This essay was published by Tropics of Meta on Nov. 3 2020. Original essay can be found here.

My students and I say goodbye to each other multiple times during our last Zoom meeting. Some strange feelings—not so much sadness as longing—linger across the little screens that show our faces. Those feelings are weirdly poignant, since we have only known and seen each other for eight weeks before our “Transpacific Solidarities, Asian American Encounters” literature course was transitioned online in mid-March; in some senses, we are still strangers to each other who lead different lives in different places outside the class. Yet, we are also connected by our shared exposure to Asian American and Pacific Islanders literature in the past thirteen weeks. This provisional connection—what Sarah Ensor calls “pedagogical kinship” —will soon disappear, not in the way it normally does but in a quiet, unnoticed way that marks many unmourned deaths lost to the pandemic.

Amid the disaster, we read and engage. I know both my students and I are very lucky.

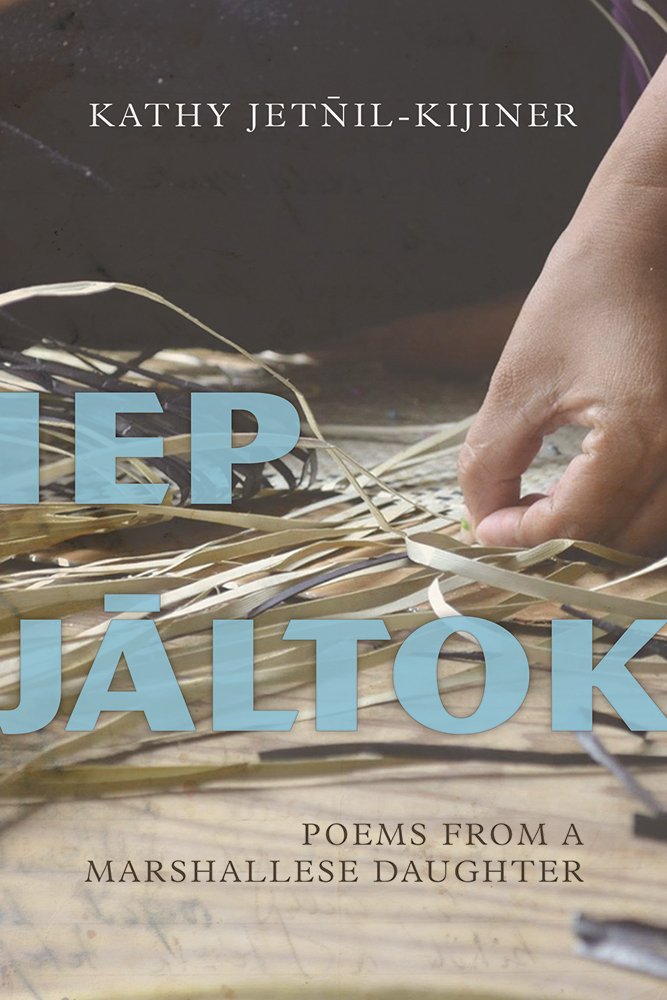

For our last meeting, we read Kathy Jetñil-Kijiner’s Iep Jāltok: Poems from a Marshallese Daughter (2017). Born in the Marshall Islands and raised in Hawai‘i, poet Jetñil-Kijiner is a mother, teacher, and activist who speaks out against the climate change and nuclear colonialism that have been hurting her people and islands. Located in the central Pacific Ocean, the Marshall Islands, like many other Pacific Islands, endured serial colonization. In the sixteenth century, the islands were “claimed” by the Spanish Empire; in the late nineteenth century, they were then sold to the German Empire. During World War I, the Empire of Japan occupied the Marshall Islands—a situation “resolved” near the end of World War II when U.S. Marines and Army troops landed on Kwajalein atoll and “saved” the islands from the Empire of Japan. After WWII, the Marshall Islands, along with parts of Micronesia, were administered by the United Nations Security Council as the “Trust Territory of the Pacific Islands,” which, in reality, was controlled by the United States.

The end of World War II saw another colonial nightmare in the Marshall Islands. Between 1946 and 1958, the United States detonated more than sixty nuclear bombs in, on and, above the Islands. The nuclear weapon tests vaporized many isles and caused forced relocation of hundreds of Marshallese people. The radioactive materials released during the tests contaminated the lands and water, and they continue to debilitate the bodies of the islanders today.

It is to these colonial wounds—their intergenerational trauma and toxic legacy—that Jetñil-Kijiner’s Iep Jāltok responds. Yet, Iep Jāltok is not just about exposing and bearing witness to irreparable harms. The poetic voice in the collection narrates stories of destruction and creation with tenderness; it conveys the poet’s forward-dawning vision as well as her yearning for the resurgence and recreation of the Marshallese culture. As Jetñil-Kijiner informs her readers, in the Marshallese language iep jāltok (yiyip jalteq) means “a basket whose opening is facing the speaker.” A symbol of generosity, iep jāltok also signifies Marshallese girls who represent “a basket whose contents are made available to her relatives”—an embodied image of Marshallese matrilineal society.

Throughout the collection, Jetñil-Kijiner weaves together Marshallese mythologies, the land/seascapes of the islands, and the interconnective kinship between her people, the islands, and the sea. The poetic weaving creates a basket that holds stories and resilience, gifts that generously flow to the Marshall Islands, the readers, and the world. As the last required text on the syllabus, Iep Jāltok sends a powerful message to my students and me when we cannot know what the future looks like, when racialized hatred, sickness, and premature deaths are what we see and hear every day.

During our last Zoom meeting, I invite my students to choose a word to describe their emotional states. A student picks “disappointed” because her summer internship offer was withdrawn; another student picks “surreal” because this is her last year in college, a year of accomplishment and celebration turned into a dystopian global lockdown; still one student says he feels “grateful” because many of his professors are being understanding and he has cultivated new hobbies such as gardening. I also share with my students my chosen word—“insecure”: I did not feel safe when the outbreak in the U.S. first started and my partner and I were among “those Asian people” wearing masks in local grocery stores. I am also concerned about life after graduation and about not being able to visit back home in Taiwan over summer or to renew my visa. Mundane as they are, these feelings speak to the incommensurable effects of the global pandemic. Feelings demand articulation—not in order to be validated but to be given a form so that they can be shared. So that we can hear them, their unique ordinariness and density.

“Ordinary” feelings also abound in Iep Jāltok. Among the poems in the collection, I am particularly drawn to “On the Couch with Būbū Neien.” This narrative poem tells the story of the poet’s visit to her būbū (her grandmother) in Majuro, a large coral atoll home to the capital of the Marshall Islands. Compared to other poems in the collection that are more creative in their form and language, “On the Couch with Būbū Neien” might appear to be plain, simply narrating the poet’s interactions with her grandmother. Readers learn that būbū Neien cannot speak because of her tongue cancer— “words / are ripped / from the belly / of her throat / before they can be born.” Nor can Jetñil-Kijiner speak fluent Marshallese, a native tongue that the English-speaking poet buries “beneath a borrowed one.” Connecting the loss of tongue (to cancer) and the loss of language (to colonialism), Jetñil-Kijiner invites us to envision radiated toxicity, colonial injuries, and broken bodies that collectively paint the wounded landscapes and seascapes of the Marshall Islands.

Still, streamlets of hope flow quietly beneath the narrative language of the poem. Hope, as one of my students points out in her written response, is hidden in the “small bundle of embroidered handkerchiefs” given to the poet by būbū. We then discuss the nonverbal communication between them: the giggling of būbū, her soft palm over that of the poet’s, and the sudden “sunlight” —feelings of gratitude—shining upon the wearied heart of the poet.

Disturbing yet hopeful, “On the Couch with Būbū Neien” makes me think about the limit of language, as well as the limit to the loss of language. While Jetñil-Kijiner acknowledges the painful loss of a (native) tongue, she also brings to visibility the singular, profound feelings whose affective contour is elusive to any linguistic hold. There is something hopeful about it. Hopeful not because what is lost can be recovered, but because an irrecoverable loss does not determine one’s sense of self and future.

Towards the end of our online discussion, my students and I are dwelling on the idea of “gifts,” which is implied in two concrete poems in Iep Jāltok taking the shape of an open basket. I ask why Jetñil-Kijiner places each basket-poem at the beginning and the end of the collection, and how the connection between these two poems enlarges our understanding of Iep Jāltok as a whole.

One student mentions that while the first concrete poem highlights the offering of individual Marshallese women and the matrilineal legacy, the second one extends the idea of offering to the nonhuman land/seascapes of Marshall Islands— “a lineage of sand / a reef of memory” —as if the Islands and their inhabitants, human and nonhuman alike, have so much to teach and give to this world. Another student comments that the gifts offered by the Marshall Islands are different from the “gifts” offered by the United States when it “liberated” the islands from the Empire of Japan. The gifts of the Marshall Islands do not come with debts or conditions, but flow with grace and gentleness towards the poet, the islanders, and the wounded oceans and the islands themselves.

After thirteen weeks of collective reading, I notice that my students have grown more confident and comfortable expressing their thoughts. They develop more curiosity for this world, its violence as well as gifts. They have become more empathetic. I’ve always believed that the engagement with literature depends on many predetermined conditions. Many of these conditions entail the reproduction and accumulation of cultural capital. That is, the reproduction of privileges. With this belief in mind, I teach my first ever literature course, reading with my students while modeling a form of critique and engagement for them. I hope that through our collective reading experience, we will eventually become more capable of imagining and understanding various levels of loss endured by others, especially those whose histories are aggressively erased. We might find a language, too, to articulate the limits to that loss and to our imagination. That is, we will come to term with the fact that we are not always able to fully comprehend the abysmal depth and crippling weight of someone’s loss. Yet still, we continue nurturing our sensitivity to signs of resilience.

Although the pedagogical kinship we cultivated over the course of the semester is provisional, our shared exposure to affective cultural texts and the precarious worlds they portray generate enduring effects on all of us. Among them are the gifts we receive from each other, and from Jetñil-Kijiner. Gifts that teach us to listen to peoples and cultures that we don’t know, and to care for this injured world with patience and tenderness. If the global pandemic has drained much meaning out of this world, these mutual gifts sustain our ordinary acts of meaning-making, despite how small and elusive they seem to be.